Introduction

These are the memories of a country child recalling his school years at Kog at the end of the

1960s and in the first half of the 1970s. Kog (the parish of St Bolfenk) lies in eastern Styria,

Slovenske gorice – Prlekija), in Slovenia – at that time still occupied by the Yugoslav army. The

memoirs reveal the great dilemmas and traumas of country children when they started going to

school, and at the same time open up the painful topic of ideology and education. At that time the

state was controlled by the dictatorship of the one and only Communist party. Rural areas were

particularly neglected, under the pressure of the party's boot. The party wanted to destroy religion,

tradition and in the end the language of Slovenes as well. After 1945 the authorities reduced the area

of agricultural land to a minimum and thus forced farmers and above all young people to move away

to the towns, while many also went abroad to find a living. Why did the party want to achieve this?

Because in alien places it was easier to force Communist ideas and Serbian unitarianism on young

people, and tear them away from the traditions of their predecessors and their parents. Also from their

culture, which the Slovene nation had preserved for many centuries, including linguistic features such

as numerous unique dialects and the exceptional dual form. Politically and ideologically the most

vulnerable and the most strictly controlled were the media, the schools, pupils and teachers. But

because resistant farmers did not so easily let go their own tradition or their Christian faith, grown-ups

and children alike lived a double life, a kind of mixture of millennial tradition and a cruel

denationalizing Communist militaristic utopia. During the entire period of his education, a total of 17

years, the author of the following text only once met one of his teachers in church at mass – and that

in a country where the majority of parents and children were religious. The great majority of teachers

renounced the majority tradition, the faith of parents and pupils. Some teachers avoided church and

religion out of conviction, others for the sake of their career, while the rest did so out of the fear of

losing their job –that is, for the sake of survival. Not daring to cross the threshold of a church, these

lived their spiritual life secretly, on the inside, while they sent their own children secretly to distant

parishes to be christened. These memoirs describe how country children experienced this duality,

these contradictions, through the school system and rural culture. Even today one cannot write and

speak openly and publicly about those iron times when differentness and tradition were oppressed –

there is also a lot of self-censorship and fear. For after a short interval, in 1991 and 1992, the former

Communist authorities regained control of politics, the media, culture and education, although then in

the independent state of Slovenia. The old models, prejudices and fears are again returning among

people, only that the methods of intimidation are more sophisticated.

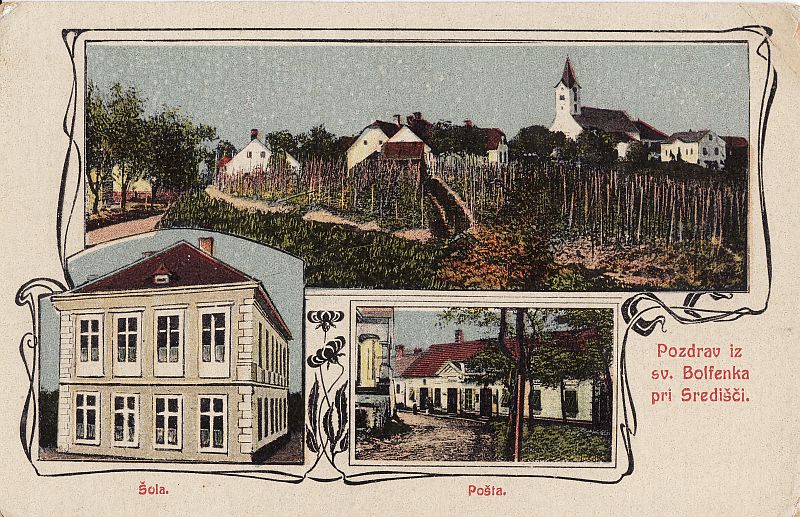

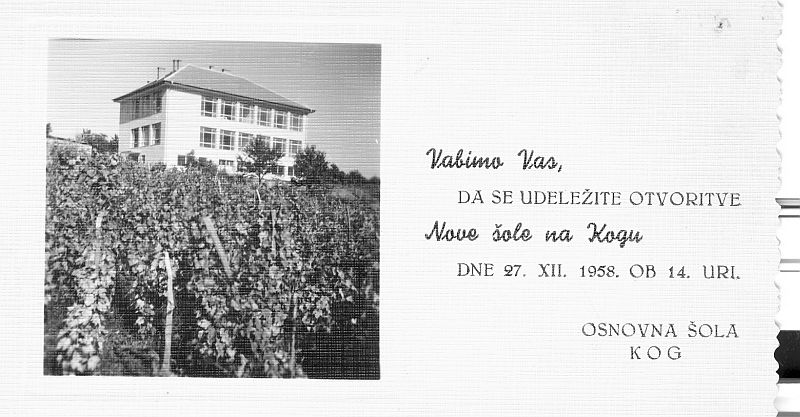

This text was published in "Memories of school" in 2009 on the 50th anniversary of the school

building at Kog. During the Second World War the village of Kog was completely destroyed (most of

the houses, the school and the church); it took a long time after the war for these wounds to heal.

Since we do not choose the place and time of our birth or the ruling ideology, the text is generally

critical, but to a large extent shows all of us – pupils, teachers and parents – as victims of a certain

period and system. At the same time it proclaims that it is possible to remain a good person, even if

the authorities demand morally questionable actions from an individual. People also make use of

some defence mechanism which protects them against the sick measures of this or that totalitarianism

and its ideology. Many were surprised that the memoirs were published at all. But truth and injustices

must not be forgotten – though of course, we can forgive one another for the injustices. Forgive, but

not forget – otherwise, the evil will be repeated. The contents here are not offensive, for the purpose

of these memoirs was to tell the truth, yet in a respectful manner. No-one is perfect, and this can also

be the charm of life.

Memories of my school years at Kog

In 2009 it was 40 years since the generation born in 1962 first crossed the school threshold. For

country children from the Kog school region this was a particularly big culture shock, a step into a

completely new world. We dikline and čehi (girls and boys), accustomed simply to the farmyard at

home, to life on the pasture, in fields and meadows, playing among the hens, gudeki (pigs), and cows,

in simple hiže (houses), in the safe shelter of a family that spanned all the generations, in those days

mostly without TV and only the occasional wireless, etc., were suddenly transposed into a huge

building (school), a new order of things, into using standard Slovene, where you could no longer

gučati (speak in dialect).

I will describe completely subjective experiences, my own understanding and memories of those times, and that because of a happy childhood, full of both good and less good experiences, which left a deep mark on my future pathway through life. Right at the beginning I apologize for any mistakes and inaccuracies, and occasionally some less pleasant memories. After all, life is a mosaic of the beautiful and less beautiful, wrapped in a veil of mystery, of the miracle that we are such people as we are, here and now. I believe that somewhere in the depth of our hearts we all wished for the good of one another, both the terrible teachers and the pupils – but it's also true that we didn't always manage this. Both aspects, the good and the less good, are worth consideration, and if at this distance in time we can accept both good and bad, we can say that the teachers successfully achieved their mission, and this is their greatest reward. A teacher can be proud if she/he gives their pupils courage to express their own genuine view of their relationship in the period and the external circumstances that essentially coloured that relationship.

A big building – new rules

For many children of this rural community the interior of the school building was quite an alien

environment. The school had huge corridors, stairways, big rooms with polished parquet floors, white

walls and huge windows, water that flowed from taps in the wall, white porcelain toilets that seemed

so clean and sterile that we felt awkward using them. This was a building where you wore slippers,

where everything was clean, and a special order ruled, while our simple homesteads were

insignificant and far from school. The smoke from the chimneys of our hiže led us in thought to our

parents sitting at the table, to a simple but tasty lunch, where there was no questioning, no homework,

and household tasks suddenly became attractive, even desirable. But the linguistic leap was even

bigger. Naturally during the breaks we children smo gučali and se spomijali

(spoke and chatted in

dialect), but during school lessons we had to use standard Slovene. We had a vague idea about this,

but all the same it did strike us as odd at first why we couldn't just

spomijali tak kak dumah (talk as

we did at home) during lessons. The teacher asked me why I spoke in dialect, and I answered that it

was nicest in dialect and that was how they taught me at home – after all that was true. In those days

we didn't attend kindergarten before school (for us the Slovene word would mean a "little garden")

and so we were transferred to school directly from the farmyard as it were – which wasn't necessarily

a bad thing.

Sneaking, copying, whispering, etc.

It is characteristic of every human community that some of the group sneak on their fellows to the

authorities, to teachers, to the church, saying they cause conflicts in the community, etc., and in this

way they feel they are carrying out an exalted mission. It was a similar situation with us, but we soon

discovered the "denouncers" and more or less skilfully avoided them. In the lower classes they

actually revealed themselves, since every day they put their hands up in the style of "Comrade

teacher, he hasn't done his homework (they even checked our satchels), he hasn't got his slippers,

he's dirty, he was smoking", and so on. But as the years passed, most of the "goody-goodies" realized

that it wasn't worth it, and we even became friends. Among most of us in the class there prevailed an

unwritten solidarity, and when we stood helplessly in front of the blackboard, in some way we tried to

help each other – but this was very dangerous, because you could soon find yourself in front of the

blackboard and getting a blow into the bargain. Help was somewhat easier with written homework,

although some hid their tests. They put a girl next to me who wasn't exactly keen on school, but

during written tests she "collaborated" quite successfully with me and some months later the teacher

even praised her highly in front of the whole class, saying how much progress she had made. I felt

proud of myself, although I didn't tell anyone else about my pride, that wouldn't have been safe for

the girl either. I also never said a word about this to her. Such "help" could have been understood as

encouraging laziness, cheating – but I felt her dire predicament as a maze which she didn't know how

to escape from – constant punishments, humiliations,– but why? Everybody has some kind of calling,

is good for something, but even today schools don't really discover these talents successfully. Junior

school after all is not an academy, it ought to be aimed primarily at the basics, at preparation for life,

and preparation for choosing a profession. I remember a schoolgirl (sad to say she met a tragic death

some years after finishing school), who also didn't really enjoy school but on one occasion she

surprised all of us during a music lesson with her exceptional voice and singing, and her knowledge of

folksongs. That schoolmate was small and shy, while her mother was a big, strong woman. I know she

once grabbed hold of me and sat me down beside her daughter to do our homework together. In those

days school psychologists or even teachers would quite quickly transfer somebody to subsidiary

school, as we called it then. But many didn't belong there, they were somewhat neglected, and lacked

socialization - which of course wasn't their fault - so it was more difficult for them to manage the

material at school, or they needed a little extra help. Some of them we missed (since we knew their

difficulties, which could have been resolved), but at the same time we were secretly afraid that all of

us would soon end up in schools for special needs.

Mischievous moments, the way home from school

There was plenty of fun during the breaks, on the way home from school, on school trips, and

sometimes even during lessons. We really quaked both before and during medical check-ups and

vaccinations. I remember it was precisely a doctor-to-be who was most afraid of the burning prick of

the sterilized, red-hot needle we felt was a butcher's instrument. We were also very bashful – standing

in just one's underpants in a queue in front of the doctor – hm, and with girls present. After fights, we

always threatened that such-and-such a cousin or elder brother would come and give us all a good

thrashing; the typical sentence ran, "You just see, my brother is training karate, my brother is in the

army and ..." We also collected Koloys navy cards (with Koloys chewing gum - small pictures with a

description of ships from all periods) – these were the main item of our commodity exchanges and the

dream of small Prlekija "sailors", hardly any of whom knew how to swim, and the sea we had seen

merely in some picture. We collected bottle-tops as well, from "Coca cola" I think, where you could

supposedly win a katrca (Renault 4). That was the period of Karl May, Vinetu, cowboys, Germans

soldiers, Partisans, Bruce Lee, Miki Muster (writer and strip illustrator for children, the strip heroes

are: Zvitorepec [foxy fox], Lakotnik [hungry wolf], Trdonja [turtle]*), etc. Comic strips weren't

exactly approved of by teachers, who considered them trash. At that time people in Slovenia were

sharply divided along the lines of the cult film (western) "The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". I know I

sold my sketches of ugly, haughty German soldiers for quite a good price to an older boy. We boys

were more adventurers, while girls in the higher classes were secretly reading romantic novels - it was

entirely understandable that we boys didn't like that, our approach was of course rather different. We

couldn't compete all that much with the teachers but an opportunity came when we could raise our

rating at least a bit - for example, while playing chess – where the teachers accepted a defeat with

dignity. The best thing was when lessons took place in front of our parents, this happened perhaps

twice for a lesson – at such a time we knew there would be no angry words, not to mention blows. We

wanted to have teachers like this, which was also proof that teaching could have proceeded with less

stress. Our notebooks, especially the boys', were not exactly a fine example of aesthetics and

cleanliness. These were dog-eared notebooks, full of torn pages – sometimes we did our homework

quickly at school, on the pasture among the cows and beside the fire.

The following incident, which

actually didn't happen in our generation, is worth mentioning for its telling character. The teacher of

Slovene regularly checked homework. It was the turn of "Franček" (made-up name), the teacher was

waiting, but Franček didn't want to take his notebook out of his satchel. The teacher was cross, asking

why he didn't show his homework. Franček answered that he had done it but didn't dare to show it.

They went on arguing like this for a minute or so. Finally Franček, his face as red as a lobster, did pull

his notebook out of his satchel. The teacher started to leaf through it, and then realized it was sticky

and had an unusual smell, a "pong". The questioning started again, this time about the reasons for the

sticky notebook. In the end Franček got even redder and mumbled that he had written his homework

on the pasture, but while he was writing, the cow Liska had strayed into the neighbour's maize. He

had to jump quickly after her to drive her back to their own meadow. Meanwhile another cow had

come to his satchel and peed on it. Back at home he spent all evening drying his notebooks and books,

but he couldn't do any more than this. All the pupils were listening like rabbits to this dramatic story,

quite dumbstruck, and then they all began to giggle. You could conclude from this that cows

obviously pee on school as well.

The following adventure is extremely instructive, but comes from

another Prlekija school. The "stupid ones" should stay at home. There was panic in the staffroom,

since the school inspector had announced his visit. Since the school wanted to appear exemplary, so

the village wouldn't be nicknamed "Butale" (village of fools), the school head decided that the most

stupid pupils (butasti) with poor marks should stay at home. The next day the inspector was slowly

approaching the school on his moped along a dusty macadam lane. But a few kilometres short of the

school his moped suddenly came to a spluttering stop beside a pasture. The comrade inspector bad-

temperedly tried to start the engine, not knowing what else to do. He was simply in despair and wet

with perspiration, his hat pushed right back. All this disappointment was observed at a safe distance

by a boy who was looking after cows on a nearby pasture. Seeing that this gentleman was in dire

distress, he came to him and asked if he could help in any way and looked to see what was wrong

with the moped. The inspector didn't actually trust him, but he didn't have much choice. The boy set

about repairs using a countryman's commonsense – first he looked to see if there was petrol in the

tank, then tested the flow of petrol, checked if the sparking plugs were working, and then the screw

with the jet, which allows petrol and air to come from the carburettor into the cylinder. He noticed

that the jet was blocked, so cleaned it with a grass stalk, turned it back into the carburettor and the

moped started like a rocket. The disbelieving inspector simply glowed with happiness, since he felt

ashamed of having to remain stuck in the middle of the pastures, not knowing how to repair a moped.

What would those bright young women teachers say? The inspector sat astride his bike and heartily

thanked the shepherd boy, at the same time praising him for being clever. He wanted to drive off, but

then remembered that the boy ought to be in school. The young country genius, not knowing who he

was talking to, replied that the teachers had ordered that on the day of the school inspector's visit all

the "stupid" pupils must stay at home. The inspector gawped at him, wanting to make some comment,

but then with mixed feelings in his head rather set off quickly towards the white school building,

where all the teachers that day were incredibly well-dressed and friendly towards the pupils. We can

just imagine what embarrassment and how many jokes the school and village were exposed to that

day. School education and real knowledge for life often don't go together. All too often we judge

people simply by their success at school, while we live from the services of "stupid" boys, who for

instance repair our vehicles and machines when these, to our great disgust, let us down.

But let's go back to our area. In those days there was school on Saturdays as well (in the first class),

and we walked to school, along macadam lanes, meadows, slopes, vineyards and forest paths, often

barefoot or wearing batači (simple plastic boots) – we used to wash our muddy

batači in the pool of

Štefek, the gravedigger. There were no telephones then, let alone cell phones, - so in this respect we

were freer than today's generations, and at times on the way home we chose longer "shortcuts". These

were paths of exploration and childhood dreams, as well as some mischief. Our hands, legs and

especially knees were full of bruises, scratches, stinging dusty wounds, scabs and craters. The rare

cars completely covered the macadam lanes in dust. In winter we revelled in innocent snowy delight,

as fingers ached with cold, and icicles dangled from our noses, and sleeves were full of snot. When

we had to set off early for school in the dark, we felt quite afraid, but we kept quiet about that in front

of friends, and especially in front of girls. At times on the way to school a kind-hearted farmer met

me, and loaded me onto his horse-drawn cart, so I didn't have to leg it to "Bolfenk" - that was a really

super day. Once the journey to school was simply in "God's" hands, since the priest stopped me, only

he wasn't driving the car, but instead his short-sighted cook, with thick-lensed glasses on her nose –

she had considerably worse eyesight than me – she wore glasses, then almost obligatorily,

permanently. The problem was mainly that she hadn't passed the driving test - the priest was only

teaching her the skills of driving. We proceeded in a slalom, at times with violent slowings and

accelerations, while behind us drifted a huge curtain of smoke due to the macadam surface and the

overburdened engine. The cook was bright red and clinging to the steering wheel in fear. The priest

was sweating, waving his hands, correcting the steering wheel, and the engine at times roared, the

gearbox scraped, but all the same we arrived safely at school – I was immensely relieved on getting

out of the car. The authorities soon moved this generally friendly priest to another parish. It was said

he greatly corrupted the young, since at mass he praised life in the USA too highly, which in those

times was a terrible sin. The USA was on the point of extinction – at least that's what they taught us.

Places then still had their old names. In the local dialect we didn't go to Kog to school, but we said we

went to "Bolfenk" (Saint Bolfenk). The way to school and so our world we still understood and

recognized through the seasons, jobs on the farm, and the cultural and natural heritage of our villages.

We knew when and where which pear, cherry, plum and apple trees bore plenty of juicy fruit, which

vines had sweet grapes, etc. We knew in which abandoned house an owl nested, which dog would

bark at us, which man or woman would give us a friendly greeting. Sometimes we indulged in a

cigarette made from dry leaves, sometimes we brought to school children's pistols from Italy. But a

check of pockets and satchels was also made, and consequently the plunder of a "dangerous" weapon,

of plastic or paper bullets followed, and blows fell so that there was more "smoke" than from cowboy

pistols. Činklanje (throwing coins on a line), playing cards, fights,

occasional impudence, the older

ones challenging the younger ones, or the stronger challenging

the weaker, etc. – none of this was

strange to us, but mostly we respected at least a minimum threshold of tolerance.

No society can completely remove social differences, and our youth too was marked by these or other

distinctions. But generally this didn't disturb us children very much, if somebody worked harder,

learnt diligently , he also had more – so we thought, and so we were taught – but it wasn't always so.

Our elders often commented, "Ja toti je v partiji, zoto mo teko penez."

("Yes, that man is a member of

the Communist party, that's why he has plenty of money."). The differences were even bigger between

country and town children. Yet we felt that possessions or status were not everything, that one person

can buy only bread, someone else even a sandwich, while someone else would stay hungry until he

got home. All the same you often heard the request, "Give me a bit of bread, etc".

The way home from school had a special charm, it meant spontaneous association, and this was a real

school for life – how to live with each other and beside each other, how similar we were and yet how

different in small details. We grew up together, in some particulars we knew ourselves better than our

parents knew us. Through the school process we revealed to each other all our virtues and faults. We

made unspoken alliances, had occasional cockfights, and small tribal tensions for dominance. And of

course we often didn't know how to overcome wrong school models, divisions, general prejudices,

stigmas, and sometimes one would cause another painful humiliation, social exclusion. There were

also differences on the basis of social status (of wealth and poverty, although formally we lived in a

society of equality) and differences on the basis of a frequently distorted picture and unjust procedures

in the educational process. We also brought particular prejudices from home. But as the years passed

we got on together, and our youth and being together on the way to and from school to a large extent

surpassed psychological, social and school prejudices and differences. On the way to school we also

used to meet people who definitely stood out from the ordinary; they were village characters. For

instance, the elderly, extravagant teacher of our parents. She wore a black hat under which stuck out

her long and curly white hair. She was dressed in a broad black dress, which reached to the ground.

An imposing old lady, from some "ancient" period, she slowly tapped along village "Bolfenk" with

the help of a stick. We younger children were quite afraid of her, nowadays you meet such figures

only in films. Various stories circulated about her, for instance, that she washed in milk. We also used

to meet a smallish man with a big humpback and a stern face. Some naughty child had taunted him

and because of his bad experiences this man didn't show much sign of friendliness towards

schoolchildren. But if you greeted him politely, there was no difficulty. According to what mother

said, he was a really nice man, and very clever as well. Sometimes we met a roguish drunkard, who

greatly frightened us boys, - he reached into his pocket for his jack knife, threatening he would cut off

our masculinity – at this we took to our heels, so you couldn't see us for dust.

Discipline and punishment

In those days methods of upbringing in the village and at school were the strict ones from the first half

of the 19th century – at school we were more often beaten than well-fed. So we soon accepted school

rules, even if they seemed incomprehensible, too strict, unnecessary, sometimes humiliating, and

some were ridiculous, especially for children used to practical country common sense. If I'm honest,

school insulted me to the depths of my soul the second day in the first class, when I was beaten for the

first time (I think this was also the first physical punishment in front of our class). The reason for the

punishment stretched back to the time before school and was the consequence of defence in a child's

fight. Even nowadays older people say that children have a rihtar (judge) behind the fence – in this

case it was so, but ... The teacher called me, "Vičar, come here!". I thought this didn't bode any good,

and remained sitting rigidly on my chair. Then she threatened, "Do you want me to come to you?"

That threat got me to my feet and I immediately stood in front of the teacher's desk. She took off my

glasses (even now her movements roll like a slow film in front of me), and then the blows fell, my

face was burning hot, I fell into a world of pain and could hardly see. I walked home alone, ashamed,

since my schoolfellows had gone on ahead and told my mother about my punishment. Mother knew

this was an unnecessary and unjust punishment for me and comforted me, which was very important –

a shelter from the previously unknown experience of public lynching. Although we didn't always

study at home, or do our homework, and we didn't always listen during our lessons, we managed to

rescue ourselves according to the logic the French live in France, or we read out unwritten

compositions from our head, etc. but the results could be very concrete. So one of my schoolmates,

without any bad intentions, answered the question, "Who lives in Bosnia?" with "Bosnians". In a

moment he got a heavy blow that sent him reeling and made him feel sick. He had deduced the

answer in a purely country way, but because the state at that time was politically and ideologically

relentless, the concept of "a Bosnian" was not to be mentioned – not even in innocent peasant logic.

How terrible it must have been to deal with the Slovenian language and the then impossible methods

teachers, the following absurd experience of a girl from Slovenske gorice also tells.

For a few days she was

absent from class due to an ear infection. When she returned to school, the teacher asked her

why wasn't she at school? The girl answered:

"My ears hurt (vüha so me bolele)." Mrs. teacher asks her one more time:

"What did you say?" The girl fearfully answers: "My ears hurt (vüha so me bolele)."

At that time, the furious teacher slapped the girl brutally and commented,

to correctly say ears ("ušesa") and not "vüha"!

At times we had to punish each other physically. You hit a schoolmate, but of course quite gently, and

then the teacher threatened that she will take over the punishing and you hit him harder – but you felt

really awful. Later on I discovered that this principle of self-punishment came from some inglorious

island (Tito's communist camp torture and killing on island Goli otok - "Naked island") ...

You could be punished for having a pair of different socks, because of hygiene (which could

sometimes be modest on the farms, but most gentlemen and comrades both now and then have

farming roots), for smiling, for the unintentional use of dialect, often for not knowing things, and also

for real bad behaviour, indiscipline, children's violence, which can be very cruel. If we understood

this last point - punishment for bad behaviour, violence - from home, we never accepted all the other

reasons for punishment. Sometimes we stayed behind after school as punishment – when you went

home by yourself, you felt awkward, because it seemed that everyone was watching you and saying -

look at him, the blockhead. The teachers sometimes also sent us to stand in the corner – better than a

beating. But this punishment could be very humiliating as well. One schoolmate stood like that in the

corner for some hours, even during the break, and you can guess what happened to him ... but no

schoolmate ever took advantage of that event. I also remember the awkwardness when our parents

were informed very tactlessly that we stank of cows, sweat and manure – on the way home from the

meeting our mothers were blazing with anger and humiliation. That was a particular time, with

particular circumstances, a particular ideological and educational policy, a region on the very margin

of the homeland, a complicated combination of many coincidences and connections, including

personal ones. The fact that Kog was a winegrowing region was not negligible either in relationships

between people – this can bring much that is good, but much that is bad too. Physical punishment

finally ended somewhere with the Slovene spring (The Slovenian Independence War - 1991) – I think

some father even came to school and established order in the style of a peasant rebel - but this story I

know only at second-hand.

Trips

These were a great relaxation for everybody. Those of us without much to spare took some homemade

bread with tunkin meat (smoked pork from lard) with us, and some fruit juice, and somewhere on the

way it was obligatory to indulge in ice-cream. In the higher classes we forgot ice-cream of course and

concentrated more on the girls. Even the teachers were more spontaneous on trips. If we had any

small change at all in our pocket, we bought some souvenir, a ball, for example. One boy, a couple of

generations after us, even bought a hoe – a really eloquent gesture. What places did we go to? For

many years I dreamed of when we would visit the places where the generation of my sisters were

taken to (on foot to Središče, in the higher classes a trip to the Pohorje range and that by cable car, to

the dreamily beautiful valley Logarska dolina, at that time they even went to the Slovene coast, to

Postojna, to the world-famous Planica valley, etc. and before the Second World War my dad on a

school trip to Središče visited the remains of a nearby Roman road, but this was not granted to us).

But we went merely to Ljutomer, Ptuj, Kostanjevica na Krki, but not any further afield in Slovenia.

Almost every other year they took us to visit the house of our great leader in Croatia, to Stubica,

Zagreb, and so on. Well, at least it's a trip, we thought. In the eighth class, when the teacher asked the

rhetorical question whether we should go again to the house of the "almighty one" (I believe this was

a command given to schools), I plucked up courage and expressed the wish that as Slovenes we might

after all travel for once through Slovenia, and behold, a miracle – the wish was granted. We weren't

able to make up for everything – but we did visit Brnik airport, Vogel, Bled, Volčji potok, Blejski

Vintgar, etc. on a two-day trip. It was then that many of us saw for the first time quite a large portion

of Slovenia, the Alps, our Triglav, and for the first time went by boat across Lake Bled ("near

Triglav"). Why our generations had such a modest programme of trips, diverted from our native land,

we can only guess. Let's say – the generations before us lived in the liberal period of the Slovene

politician Stane Kavčič, who was removed in 1971 by the Belgrade clique because of his patriotism

(if today we use some street or road, we use Kavčič's – the irony is that now the neo-Bolsheviks are

building Titova cesta (Tito Street), while we know that Tito took money from Kavčič in 1971 and

removed him, and Kavčič will get a tiny little monument somewhere far away from people).

"Kavčič's" money for the Slovene motorway system, which we are still building today, went to

construct the Niš-Belgrade-Zagreb motorways. In Slovenia the hawks ruled again and so the school

system also chose a hard orientation. We are feeling the bad consequences even today. In these cases

it is seen how little autonomy teachers and schools had then – the ruling Belgrade set decided about

everything, even about trips. Sometimes I have the feeling that the foreign values (for example more

trips outside our homeland than within it – we visited Zagreb, but never Ljubljana, let alone ethnic

Slovene areas), which the teachers at that time, mostly against their will, had to enforce on us, have

today been really accepted by some, so that we Slovenes feel superfluous in our own native land. At

times even our own country, our tradition is foreign to us. What would people give for their own

independence, their own state, let's say the Scots, Basques, Catalonians, Bretons, Kurds,

Chechenians, the suffering Tibetans, Palestinians, etc. As writer Ivan Cankar said, "The master

changes, but the whip remains, and will remain forever; because the back is bent, used to the whip and

wanting it!"

Ideology and school

This is an unwelcome topic, but very instructive – often the reasons for unnecessary complications are

hidden here. No state, empire or political system leaves its schools, and thus its young people, open

simply to the ideals of knowledge, freedom, equality and truth, but precisely among its youth weaves

its ideological and cultural network - its value system - through schools, the media, troublemakers. It

was no different in our young days, especially since we lived in a state with one prescribed ideology.

That was a time when Slovenia was not yet a free and independent state, when Ljubljana was not its

capital but instead distant Belgrade, when there were no free elections, no parliamentary democracy,

when boys had to do their military service mostly outside Slovenia, and had to speak a foreign

language (not a few came home in a coffin), when only one party was prescribed, and one ideology,

and one political leader until his death – his picture hung everywhere. This was a system of complete

control and informing. There was no freedom of speech, of print, many books were forbidden. Parents

hid certain topics from us. The one compulsory ideology could also lead to family conflicts – one

member of the family made himself a "new" man and climbed up the social ladder, while another

remained faithful to tradition and our hills. It follows from all this that Slovenia had to submit, not

only to that one ideology but also to the foreign powers in Belgrade. Thus the whole school system

was subordinated to this political organization: we honoured one leader, we were his youth (typical of

all despots, who even in their own lifetime have set up their monuments and streets), we learnt that

the rotten west was collapsing, that external and internal enemies were threatening us, that we were

the best, that we were in a transitional period on the way to "paradise", etc. In our generation no one

any longer checked your hands to see if they were grubby after dyeing Easter eggs but they still wrote

the political evaluation which accompanied you all your life. A late teacher, a good soul, from some

other place, told me that the police always came to school after Christmas for a list of pupils who

were absent from school at Christmas. She also mentioned that any conversation in class on the topic

of traditional country feast days was forbidden. A pupil, for instance, would enthusiastically describe

what a marvellous Easter potica (traditional cake) his mother had baked, and that his aunt had come,

etc.- and the teacher in embarrassment just said yes, yes, and somehow switched the conversation to

another topic. Most classrooms were bugged by the State Security Service and just some talk about

potica could mean a punishment, the teacher being removed to another school, and so on. All these

contradictions were not really understood by us children – we were not properly aware of being

abused for political purposes. But for the sake of peace at school and at home we obeyed practically

all the demands of that time. One value system reigned at home, and another one at school, where we

drew pictures of the "great" leader, wrote compositions pleasing to the state and the system, etc. If

you kept the ideological commands, there were no serious problems, but you could break them

unawares. It was bad, for example, if someone sneezed awkwardly during a school celebration, and

someone else couldn't suppress a laugh. On one occasion I was smartly clipped over the ears and told

I had really disgraced my uncle (this uncle was part of the bureaucracy... but certainly he wouldn't

understand it like that, I thought then and still do today).There was also the case when the teacher for

a whole hour scolded and scolded a schoolfellow (we all sat rigid) terribly for playing football after

school when he ought to go home straight from school, and said he would be thrown out of the

Pioneers organization. We were all afraid, not understanding anything, and what if they do throw you

out of the Pioneers organization; we were still more amazed why so much fuss was made because

someone played football after school. The affair calmed down (after school we all fled home and no

longer went to the playing field) and was gradually forgotten. It was only years later, when we were

grown up, that we understood what the problem was. Some children had played football after school

with a young priest and nobody suspected there was anything wrong with that – but at that time it was

a serious offence (the slogan was in vogue that religion was the opium of the people), for the state and

ideology of that time intended to slowly eradicate the majority religion and the tradition of our parents

– and in the end the language too (through common Yugoslav syllabuses). In the towns they were

successful in this. That priest soon had to leave our parish. That these pressures were two-faced is

seen in a tragic happening from the Second World War, when the last newly ordained priest from our

parish had to die in the notorious Ustaši concentration camp at Jasenovac. This shows that we Styrians

always loved our native land – regardless of the ideological orientation. We children felt that and as

adults we showed it in the years 1988-1991. The same is true of our parents, our grandfathers, of the

Second World War, General Maister's fighters for the north Slovenian border (1918/19), the mass meeting

movement of 150 years ago (for The united Slovenia), etc.

Knowledge and conclusion

We received solid foundations, and particular subjects were simply excellent. The methodology was

frequently questionable – the previously mentioned harsh and unsuitable punishments, but the

professionalism of the teachers was mostly on a high level and the majority of pupils had no

difficulties with their further education.

What can I say at the end? We must certainly express thanks for all the effort and the knowledge

which the teachers gave us, while somehow forgiving each other for all the bad times. Many of them

were sufficiently strong, like that teacher mentioned above, that they overcame the ideological and

cultural stupidities of that time with their human attitude. I also believe that they all wanted to do

good, but some of them acted in a more awkward way, with less nerve. We were born into this world,

in Prlekija and at a time we didn't choose, but just for that reason the fine school moments should

remain as an encouragement for our life. All the bad and unnecessary things should be a warning that

it's always worth remaining a person with all our virtues and faults, even if somebody who has power

wants to convince us that we aren't good and that we ought to build a "new" man. We Prlekians, such

as we are, are good people, only that sometimes in our modesty we forget that. I only wish that our

school at Kog might long have open doors.

Zorko Vičar, B.Sc.

Kog and Ljubljana

May 2009

Translated by Margaret Davis

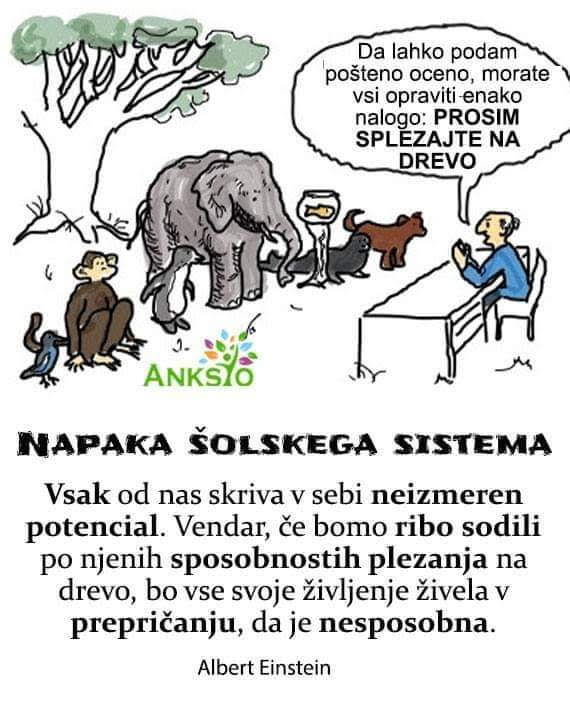

Napaka šolskega sistema

Vsak od nas skriva v sebi neizmeren potencial.

Vsi so na svoj način geniji.

Toda če sodiš ribo po njeni sposobnosti plezanja na drevo, bo

vse življenje živela v prepričanju, da je neumna, nesposobna.

Kaj je mislil Albert Einstein, ko je izrekel ta stavek?

Mnogi ne verjamejo, da je Einstein to sploh kdaj rekel ali napisal.

Vendar pa je 'modrost' v tej izjavi jasna. Človek bo verjetno dosegel uspeh

v svojih prizadevanjih,

če se bo spopadel s tistimi izzivi, ki so v njegovi moči in so znotraj njegovih zmožnosti.

"Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree,

it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid." - Albert Einstein.

What did Albert Einstein mean when he said that sentence?

Many do not believe that Einstein ever said this or ever wrote this.

However, the 'wisdom' in this statement is clear. One is likely to

achieve success in one's endeavours,

if one attempts those challenges that play to one's strengths and are within

one's capabilities.

Zagotovo pa drži njegova avtentičnost kritike mature.

NOČNA MORA Mature, ki sledi normalnemu obisku šole, nimam samo za nepotrebno, ampak celo za škodljivo. Za nepotrebno jo imam, ker brez dvoma lahko učitelji kake šole ocenijo zrelost mladega človeka, ki je več let obiskoval šolo. Vtis, ki so ga učitelji med časom šolanja dobili o učencu, in zagotovo veliko število pisnih izdelkov, ki jih je moral izdelati vsak učenec, dajo skupaj dovolj obširno podlago za oceno učenca, boljšo, kot jo lahko da še tako skrbno izveden izpit. Za škodljivo imam maturo iz dveh razlogov. Strah pred izpitom in velik obseg snovi, ki jo je treba zajeti s spominom, v znatni meri škodujeta zdravju številnih mladih ljudi. To dejstvo preveč dobro poznamo, da bi ga bilo treba na dolgo utemeljevati. Vseeno pa bi rad omenil znano zadevo, da številne Ijudi v zelo različnih poklicih, ki so v življenju uspeli in za katere ne moremo reči, da imajo šibke živce, do pozne starosti v sanjah muči strah pred maturo. Matura je škodljiva še zato, ker zniža raven poučevanja v zadnjih šolskih letih. Stvarno zaposlitev s posameznimi predmeti prerado nadomesti nekakšno bolj ali manj zunanje urjenje učencev za izpit, poglobitev pa nadomesti nekakšen bolj ali manj zunanji dril, ki naj razredu pred izpraševalci podeli določen sijaj. Zato proc z zrelostnim izpitom! A. Einstein Zapis je bil objavljen v časopisu Berliner Tageblatt 25. decembra 1917.Zgornji zapis (prevod) je bil zavrnjen v neki strokovni slovenski reviji, čeprav ga je za objavo predlagal zelo eminenten naravoslovec (prof. dr. Janez Strnad). Če se strinjamo z zapisanim ali ne, neobjava Einsteinovega razmišljanja veliko pove o (ne)svobodi in kritičnosti duha naše dežele.

Stevilo obiskov od oktobra 2002: zelo veliko